It was the bottom of the ninth inning, and I was at the height of agitation.

“Why did I do this?” I berated myself.

Even though this was back in 1971, I think of the drama every year at this time.

The High Holy eve of Rosh Hashana was fast approaching at Yankee Stadium. Every good Jew would be in the synagogue before sunset to greet the Jewish New Year. But here I was, in the press box, fists tightened over my Olivetti portable typewriter, staring down at the baseball diamond. Sure, it was the best seat in the house. But it wasn’t where I wanted to be. In just a few hours, I was supposed to be at the Shelter Rock Jewish Center on Long Island, far from the Bronx.

Could I make it home in time? The score was tied, 2-2. The Yankees had managed only two hits all day. If the game went into extra innings, I’d be out of luck.

Writing baseball was the gold standard for a sports journalist at the time. After all, it was America’s pastime, right? To cover a baseball game for a newspaper was practically an honor. This was 1971, and even though I had been a reporter for eight years, I didn’t want to turn down the chance to cover the Yankees — the New York Yankees, the Bronx Bombers, playing in Yankee Stadium, the House That Ruth Built.

And so I accepted the assignment.

It had seemed so simple. I had to be home by sundown. Most baseball games in those days took under two and a half hours. The game started at 2:04 p.m. I figured it would be over by 4:30. I go to the locker room, get my interviews, come back to the press box, finish writing my 800-word story by 5:30 p.m., drive home to Roslyn, N.Y., arrive by 6:15, get my yarmulke to cover my head, and bible, and Roz, 5-year-old Ellen and 3-year-old Mark and I walk to temple — just before sundown.

I checked my notes. The Yankees were in fourth place with the season winding down. But third place was worth fighting for. The players on a third-place team would earn $250 a man! Fourth place was worth nothing. For a fellow like Ron Blomberg, who was earning $12,500 for the season, that $250 was the equivalent of getting paid for three extra games.

He wasn’t much on my mind as the Yankees prepared for the bottom of the ninth. The score was tied, but the Yanks had generated only two hits all game. Blomberg? He had been hitless in three at-bats.

I always thought of Blomberg as more Georgia than Jewish. I had met him just once, five weeks before. And that was on the Long Island Rail Road, of all places. The Yankees were conducting a marketing campaign in Mets’ country — Long Island — to get fans to go all the way out to the Stadium in the Bronx. Traditionally, Yankees fans came from the five boroughs (well, not so much from Brooklyn) and North Jersey.

So here I am, on the train with Blomberg, whose job was to wave to fans and say a few words as it wended its way through the suburbs.

The train stopped in Ronkonkoma. Blomberg, who had complained earlier about the heat, asked the conductor to turn up the air-conditioning and said he was tired and hungry after having driven to New York from New Jersey.

“Boy, I’m exhausted,” he whispered.

Someone came in with trays of cocktail sandwiches.

And so I watched Ron Blomberg, the Jew from Atlanta, consume eight ham and cheese sandwiches. He topped the banquet off by eating a whole lemon.

Now, more than a month later, I squirmed in the press box. I just knew this game would go into extra innings. The Bombers looked bad at the plate.

A fellow named Jake Gibbs led off, though, with a single against Steve Dunning — the first hit the pitcher had yielded since the third inning. Gibbs got to second when the ball skipped off the right fielder’s glove. Felipe Alou then sacrificed Gibbs to third.

Next up was Roy White. He was walked intentionally so that Cleveland could set up a double-play situation against … yes, you guessed it, Blomberg.

What was left of the crowd of 9,177 (I guess a good many left to go to temple) was now roaring.

Blomberg, a good percentage hitter — but not a slugger — strolled to the plate, and suddenly the entire Cleveland outfield left their positions and stopped halfway toward the infield. Manager Johnny Lipon was figuring a deep fly ball would send home Gibbs anyway.

And that’s what Blomberg hit.

Center fielder Vada Pinson looked at the ball sailing over his head for an instant — and then headed for the Cleveland dugout. He knew it was over. The ball landed in deep center, Bloomberg high-tailed it to first, Gibbs came home. And the Yankees won.

Maybe I could make temple after all.

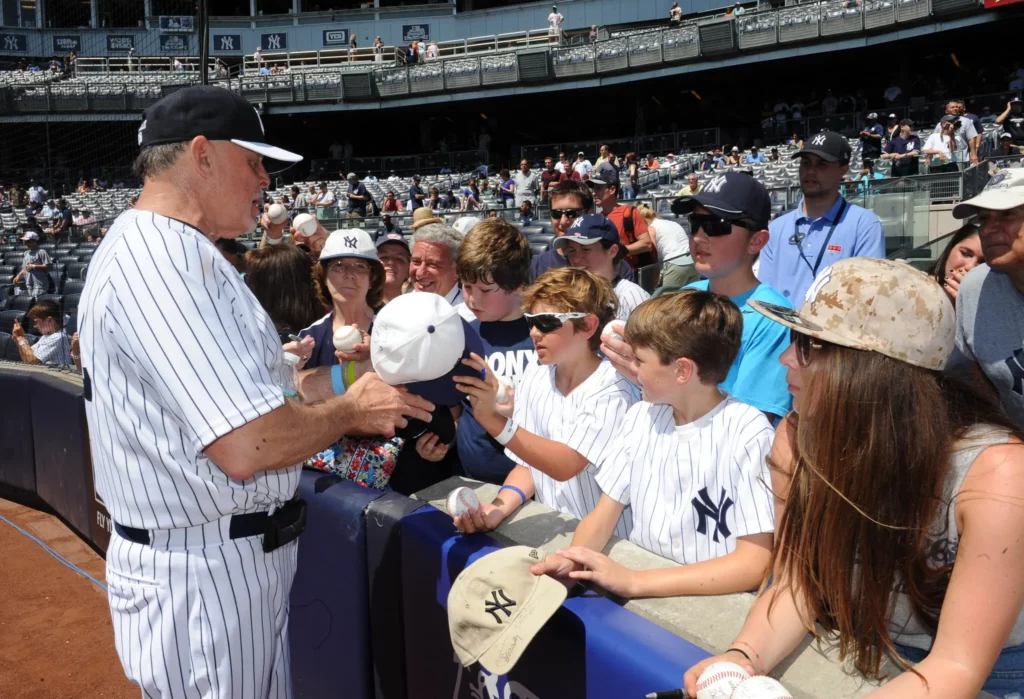

I charged down to the locker room and there was a jubilant Blomberg in the middle.

“If the count had been 3-2 and the sun went down, I would have left for temple,” he shouted.

Wow. What a quote. So he would have left the game to go to services? All the writers were scribbling on their notepads, and Blomberg looked as if he had just capped a World Series game. He was ecstatic. He was at that moment a Jewish ballplayer who had just won the right to go home and celebrate one of the most important holidays of his religion. I shared his excitement. I knew that while about 2 percent of Americans were Jewish, only about 1 percent of major leaguers had been Jewish.

“Well, Blomberg got an early celebration, huh?” said Alou.

I had my quotes, got back to the press room, typed my story, handed it to the Western Union telegrapher who sent it to The Times. And I made it to temple at a quarter to 7.

The next morning, I picked up the paper in anticipation. Would The Times, a paper that avoided religious talk back then, leave in all my references to Blomberg, his Jewishness and the holiday?

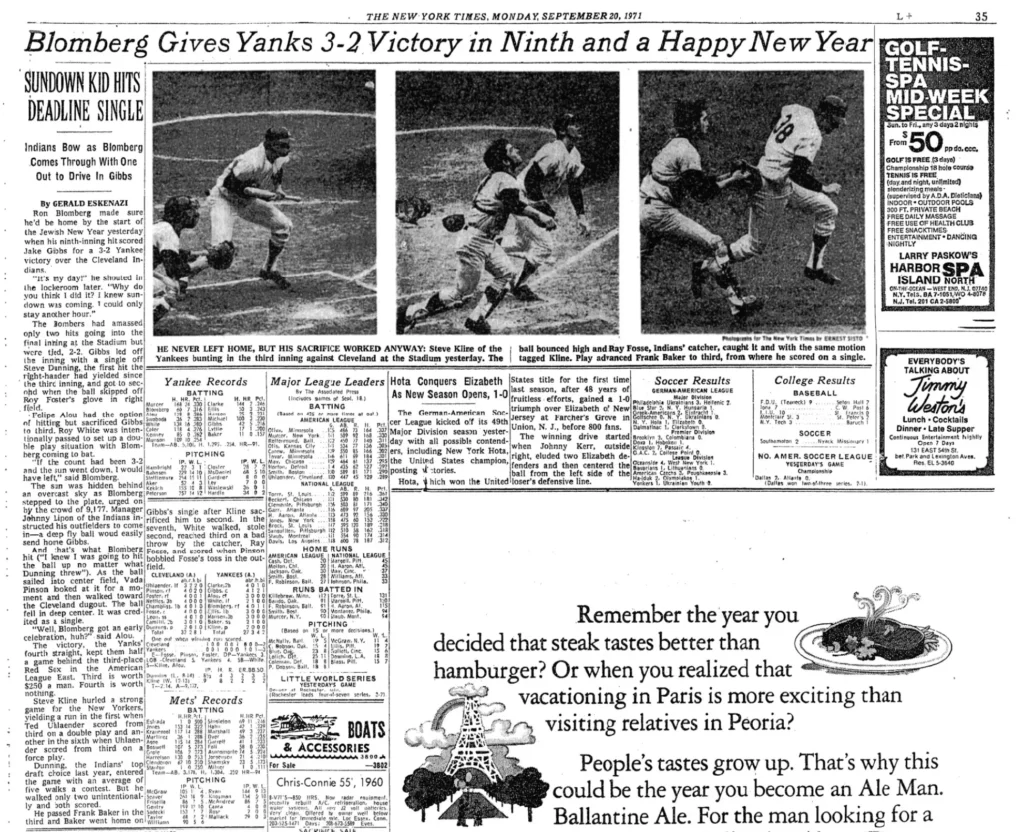

It spread my story across the top of the page.

Grinning all the way, I went back to Shelter Rock for morning services. Rabbi Myron Fenster, a key figure in American Judaism, soon gave his sermon to a temple packed with more than 700 people.

“Sundown kid hits deadline single,” he began. I was ecstatic.

The years passed and Blomberg continued his career with the Yankees until a string of injuries curtailed his effectiveness. Yet, he made the Baseball Hall of Fame, in a way, by becoming the game’s first designated hitter. The bat from that first appearance, in 1973, is in Cooperstown, N.Y.

He played his last game for the Yankees in 1976. Free agency took him to the Chicago White Sox two years later, but he lasted only one season and retired at 30.

Yet every year l remember sitting in that press box, looking down as he belted the baseball into deep center, sending the Yankees to victory and me to the temple on time.

Comments