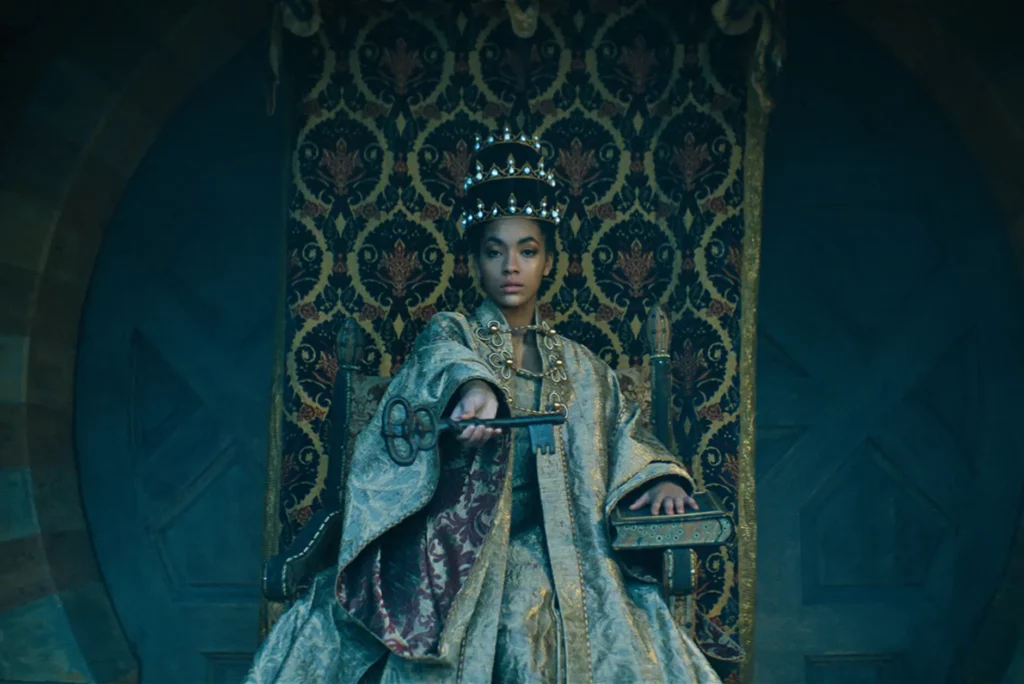

Dior’s spring 2021 haute couture collection debuted last January with a lush short film created by Matteo Garrone that opens with a tarot reading that transports its querent to a mysterious chateau populated by sumptuously dressed figures from the card deck — the Fool, the Empress, an anthropomorphized Sun and Moon — who act as signposts as she travels down one corridor and then another. The short, and the looks it showcased, which were designed by the brand’s artistic director, Maria Grazia Chiuri, was partly inspired by Italo Calvino’s 1973 novel, “The Castle of Crossed Destinies,” in which the characters lose the power of speech and can communicate only through tarot cards, and it nodded to Christian Dior’s well-documented interest in the divinatory arts, on which he particularly relied during the precarious days of the Second World War.

By the 1940s, tarot was already a centuries-old practice — it is thought to have originated in Central Europe in the 1400s, and the oldest surviving cards hail from decks commissioned in the mid-15th century by Filippo Maria Visconti, the Duke of Milan, and his successor, Francesco Sforza, and feature detailed illustrations of nobility and gilded backgrounds. These and other decks became status symbols for upper-class Italians, who used them to play an early version of bridge. The practice spread to France in the 18th century, and the cards were assigned mystical meanings when occultists, among them the cleric Antoine Court, attempted to create an association between tarot and ancient Egyptian spiritual thought. The connection proved spurious, but still, tarot took on a life of its own, with more and more mystics — the influential British occultists Aleister Crowley and Arthur Edward Waite among them — using its decks to predict the future: the Death card, for instance, might symbolize a coming period of radical change and rebirth, while the Temperance card might suggest a need for balance. The deck Waite devised, which was first printed in 1909, has long been considered a good place to start for those just familiarizing themselves with the major and minor arcana, terms used to describe the trump and suit cards, respectively.

It’s no surprise that tarot carried over into the 20th century, too — along with the advances afforded by modernity came plenty of conflict and confusion — or that its popularity has surged in the last couple of years, during which the pandemic has scrambled nearly everyone’s notions of the normal order of things. The search for meaning and direction, it seems, has never gone out of style and feels especially urgent at present. And even if we don’t actually believe in the cards, they do seem to possess an imaginative power that, amid so much uncertainty, can be hard to access in ourselves. Who wouldn’t welcome any kind of indication as to where we may be headed right about now?

One group consistently and particularly taken with tarot is artists. The decks are a sort of art object, after all, and artists are themselves in the business of making meaning. In the early 1970s, Salvador Dalí began work on a deck featuring himself as the magician and his wife, Gala, as the Empress. In 1979, Niki de Saint Phalle began constructing her Tarot Garden, a grouping, in Italy’s Tuscan hills, of 22 large-scale concrete sculptures inspired by tarot imagery and adorned with mosaic and mirrored tiles. A standout is “The Empress,” an opulent large-breasted sphinx adorned with a crown, which served for a time as the artist’s living quarters.

Now, a new generation of artists and designers are channeling their creativity by making decks of their own, ones that reflect the current era. The New York-based artist Tattfoo Tan created his New Earth Resiliency Oracle Cards as a part of his New Earth project, an immersive, teaching-based work that instructs users in both practical skills and spiritual modalities intended to help them contend with climate change. While we might associate tarot with the celestial, to Tan it can be a tool for staying connected to nature and the seasons here on earth. Accordingly, his deck features minimalist black-and-white sketches of fog, winter and drought. For her part, the Indiana-based artist Courtney Alexander is linking tarot to the politics of representation. Disturbed by how many so-called Black tarot decks, or those depicting Black characters, were created by white artists, she set out to make one that felt more authentically inclusive. The result was her Dust II Onyx deck, the cards of which are printed with Alexander’s ornate multimedia collage paintings, works rooted in Black diasporic histories and popular culture. She gave the King of Swords, traditionally a symbol of intellect, the name Papa Blade, the face of Neil deGrasse Tyson and the eyes of George Washington Carver, and the Queen of Cups, the ruler of the emotional realm, the name Mama Gourd, the face of Missy Elliott and the eyes of the poet and activist Nikki Giovanni. “The story of Blackness deserves reverence,” Alexander says, “and to be seen as powerful.”

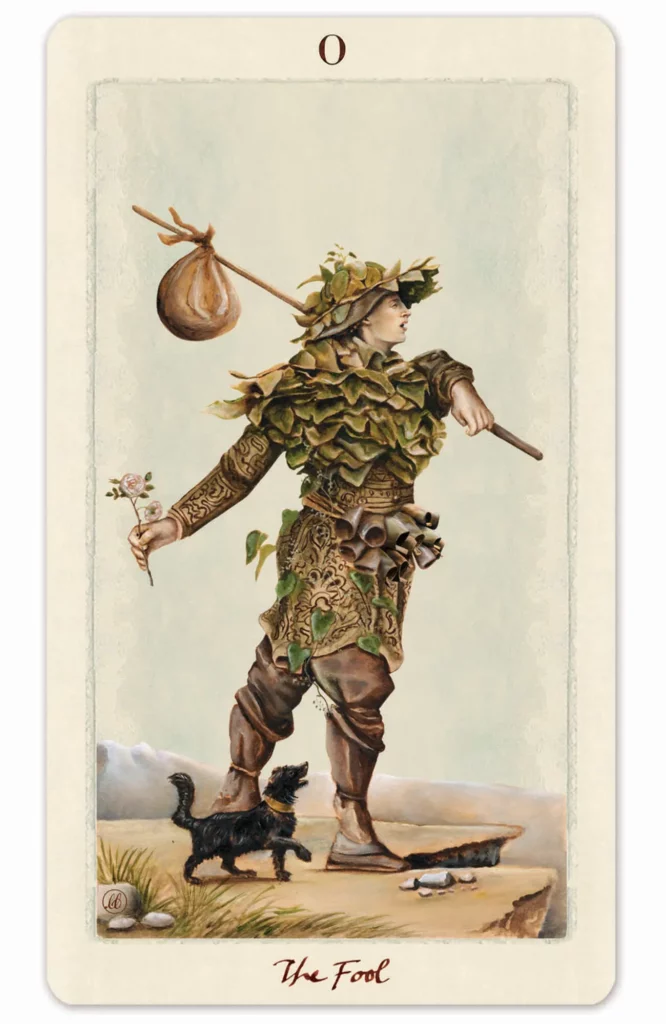

Other decks nod to various art movements. For the Michigan-based artists Linnea Gits and Peter Dunham’s Pagan Otherworlds Tarot deck, Gits studied the work of Renaissance artists like Albrecht Dürer and then did an original oil painting for each card. (Dunham did the lettering.) The overall effect, though, is rather surreal — her grim reaper is a skeleton with wings made of arrows who’s in the process of stepping on the head of a half-buried woman holding up a flower — and recall the early 20th-century Surrealists’ habit of combining seemingly disparate objects in the hope of arriving at hidden psychological truths. (Gits and Dunham are among the artists included in “Tarot. The Library of Esoterica” [2020], Jessica Hundley, Johannes Fiebig and Marcella Kroll’s visual art history of the practice.) And the artist Isa Beniston began creating her Gentle Thrills Tarot deck while quarantining in her Los Angeles apartment in 2020. Unable to access her studio, and in need of a project, she picked up new supplies at a nearby store and made hyper-colorful, Fauvist-feeling versions of the cards using gouache. She also relates to the tradition of the salon, and hopes her project will inspire not just self-knowledge but togetherness. “I think people are most joyful when they use the deck with friends,” she says. “And I love the idea that my work might be used to help build community. That’s all an artist can really hope for.”

Comments