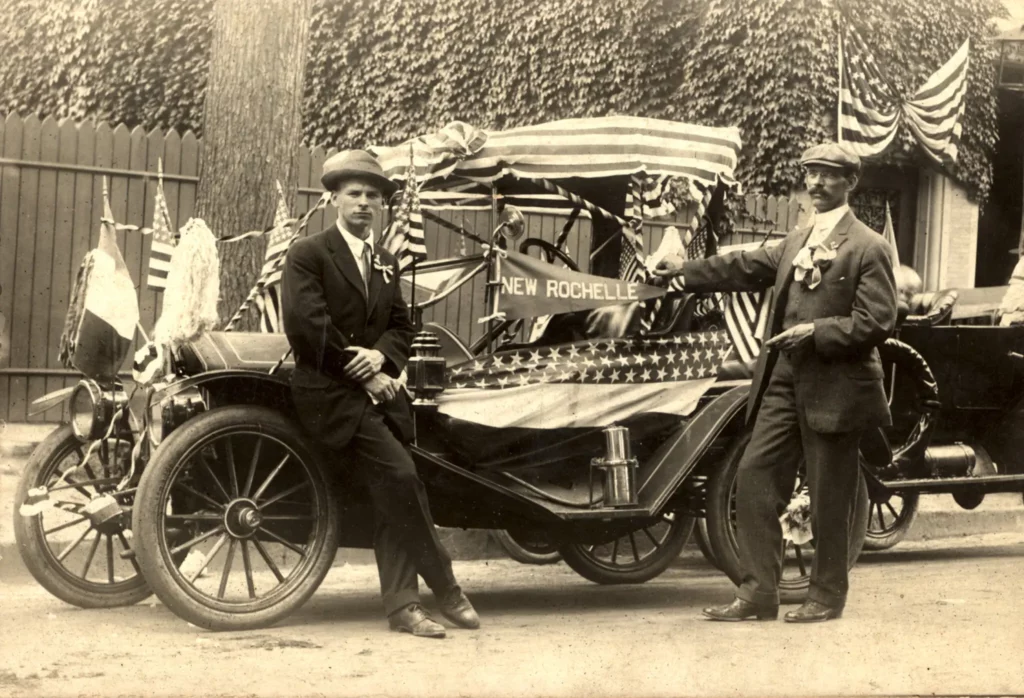

FOR ALL ITS grounding in history and its exhaustive research, “Ragtime” (1975) immediately announces itself as a fantasy. Its first few pages consist mostly of patient scene setting, reminding us puckishly of all that was different about American life in 1906 (“There was a lot of sexual fainting,” e.g.) while establishing the particulars of a three-story suburban house in New Rochelle, N.Y., and the family that lives there. Though they will all play important roles in the novel, these characters are so conventionally positioned that they are never even given proper names; they are Mother, Father, Mother’s Younger Brother, Grandfather and a child known only as “the little boy.” The little boy, we are told, has lately developed a fascination with Harry Houdini, although, being too young to frequent vaudeville houses and the like, he has only read obsessively about the world-famous escape artist, never seen him in the flesh. And in the next paragraph, a car — nay, “a black 45-horsepower Pope-Toledo Runabout” — crashes into a telephone pole in front of the little boy’s house, on that sleepy street in out-of-the-way New Rochelle; the unharmed passenger, who then comes to the front door to apologize, is Houdini himself.

One’s immediate reaction, as a fellow novelist, at least, is: Oh, come on, you can’t get away with that. You can’t possibly set your whole plot in motion via the most brazenly unlikely, nakedly manufactured coincidence you can think of and then expect the reader to trust anything else you say. But of course Doctorow does get away with it and much more; the quiet, soothing authority of his style coolly belies the audacity of nearly everything “Ragtime” is trying to do. As a writer, he had more than a little Houdini in him.

GREAT NOVELS TEACH us how to read them; “Ragtime” is no exception. It lets us know right away that the comic warp of its narrative will leave no lifelike loose end. It has the gleefully lunatic recursiveness of a “Seinfeld” episode. It’s as densely populated as the tenements it later depicts, and every character’s orbit will intersect with the others’, no matter how divergent their lives. Sigmund Freud appears in the novel for only one brief chapter, but in that chapter he will of course cross paths with the fictional immigrant street artist known only as Tateh and his daughter on the streets of the Lower East Side. Of course the man hidden in the bedroom closet of the famous anarchist Emma Goldman will turn out to be Mother’s Younger Brother; Mother will meet (and eventually marry) Tateh; the white family in New Rochelle will open its door to the Black ragtime pianist Coalhouse Walker Jr.; Coalhouse and the capitalist demigod J. P. Morgan will sit, at different points in the novel, in the same chair. Nothing is too unlikely to delight; any and all synchronicities will be permitted in the service of authorial fantasy. But a fantasy about what, exactly?

It’s not about the innovation with which “Ragtime” is most commonly associated, that of the fictionalization of real, famous people. (Here, “fictionalization” means not simply that these people are made to do and say things that no historical record indicates they ever did or said, but — much more crucially — that we are given speculative access to their interior lives, their unexpressed thoughts.) This was a bigger deal in 1975 than it seems today; according to Doctorow, William Shawn, the venerated editor of The New Yorker, refused to let any full-length review of “Ragtime” run in the magazine, on the grounds that what its author had done was “immoral.” Doctorow might well have pointed out that this supposedly revolutionary breaching of the distinction between real and made-up people had been performed many times before, by Shakespeare, if you please, among others. John Dos Passos, one of Doctorow’s aesthetic fathers, had done something similar in his novels some 40 years earlier, though he did stop short of, for instance, actual sexual congress between the fictional figures and the real ones.

Still, Shawn would not have been wrong in thinking that “Ragtime” represented something new under the literary sun. What sets it apart from other such hybrid conceptions, past and future, is how exuberantly overstuffed it is with these real-life figures. It’s not some sober, long-form, deep-dive effort to recreate the consciousness of, say, Ludwig Wittgenstein or Gary Gilmore; it’s a pageant, a parade, like one of those old photographs of Coney Island on a summer Saturday where it’s so crowded there’s no space for anyone to lie down, or a Richard Scarry-esque spread in which Tateh, Henry Ford, Stanford White, Mother’s Younger Brother, Goldman, Booker T. Washington, Evelyn Nesbit, Coalhouse, Big Bill Haywood, Theodore Dreiser and dozens of others all do their busy jobs side by side.

There’s a wonderfully, deceptively life-affirming way in which to read all this compulsive connectivity: as a pledge to the idea that, despite appearances, our lives are interdependent in ways we’re unaware of. Black, white, celebrity, citizen, criminally rich, brutally poor: We’re all one in the end, we’re all part of the great Butterfly Effect that determines human events. It’s democratizing; it’s American. And the pure pleasures of “Ragtime,” its elegance and generosity and humor, do allow one to glide along on that gratifying buzz for a while. But I think Doctorow had a more admonitory message in mind.

Father’s fortune derives from his success making and selling fireworks, flags, decorative red-white-and-blue bunting — the accouterments of patriotism. (By the time the novel ends, those innocent fireworks will have morphed into homemade bombs and then military-grade weapons; as Doctorow understands, it’s a pretty straight line.) What that patriotism tends to rest upon — then as now — is our capacity, indeed our determination, to see what (and whom) we choose to see and our conscious or unconscious refusal to see that which interferes with what we want to believe. And there’s so much we don’t want to see. Our ease depends on it.

Doctorow himself was fiercely if decorously political, a kind of gentleman firebrand. He had a side career as an essayist for The Nation, wherein he blisteringly denounced Nixon, Reagan, George W. Bush (“The President we get is the country we get. With each new President the nation is conformed spiritually. He is the artificer of our malleable national soul”), the notion of “corporate speech” and our evolution into a “national military state.” He once delivered, in his distinctively mellifluous speaking voice, a commencement address at Brandeis University so savage in its attack on “right-wing Republicanism” that one of the trustees complained to the university president on the spot.

But he knew that his task as a novelist was not to hector us — it was to seduce us into seeing. The fantasy world “Ragtime” creates is not simply one where common folks (and common readers) get dreamlike access to celebrities; it’s one where the kind of contact your average, patriotic white Mother and Father usually avoid — with immigrants, with Black people, with Communists, with the police, with Houdini, etc., etc. — is made literally, almost comically unavoidable. The little boy wishes to see Houdini and then instantly — magically, really — sees him, not from some balcony seat but doing card tricks in the boy’s own parlor; that inaugural unlikelihood opens a kind of floodgate in the novel whereby the gaps between wildly disparate American lives are closed and the veils that keep some invisible to others are dropped. Some of Doctorow’s characters are able to hold onto their patriotism in the new light of this vision and others are not.

PROMINENT AMONG THOSE things a patriot is unaccustomed to seeing clearly is the past. There’s a reason “Ragtime” comes cloaked in a kind of perfume of nostalgia, but that dissipates pretty quickly. (Even if Doctorow does retain a boyish fondness for the names of vanished things, mechanical things especially; no car or train or engine of any kind appears in the novel without our learning its full long-obsolete name.) On the subject of the rich, in particular, he is gimlet-eyed; with only a shift in tone, his signature short, wry sentences turn into hammers:

It became fashionable to honor the poor. At palaces in New York and Chicago people gave poverty balls. Guests came dressed in rags and ate from tin plates and drank from chipped mugs. Ballrooms were decorated to look like mines with beams, iron tracks, and miner’s lamps … One hostess invited everyone to a stockyard ball. Guests were wrapped in long aprons and their heads covered with white caps. They dined and danced while hanging carcasses of bloody beef trailed around the walls on moving pulleys. Entrails spilled on the floor. The proceeds were for charity.

Having established this realm of magical seeing, Doctorow then puts it, and us, to a test. “Ragtime” changes in both shape and mood in its second half, abandoning the pinwheeling movement among many perspectives and anecdotes for one story — the tragedy of Coalhouse Walker Jr. — which flies like an arrow toward its target, and from which we are not permitted to look away. Coalhouse’s mere existence as a cultured, successful Black man is something a great many people would prefer not to see; it makes sense, then, that the precipitating event in his story does not really grow out of the preceding plot — aside from the fact that it happens in New Rochelle, it seems almost random. The injustice done to him (his car is vandalized by a group of white volunteer firemen) is all the more humiliating for the fact that its perpetrators perceive it as a joke or a prank, if one with a sharply racist message. Coalhouse, though, refuses to get the message — that is, he refuses to participate in his own humiliation, despite advice from the police, from lawyers and from Father himself that the prudent thing would be to do just that. His demands are modest, his methods, as he is ignored, increasingly less so.

Comments